Netherlands

Synthesis

major macro economic indicators

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 (e) | 2024 (f) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP growth (%) | -3.9 | 6.2 | 4.3 | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Inflation (yearly average, %) | 1.3 | 2.7 | 10.0 | 4.3 | 3.0 |

| Budget balance (% GDP) | -3.7 | -2.3 | 0.0 | -2.1 | -1.7 |

| Current account balance (% GDP) | 5.1 | 12.1 | 9.2 | 8.0 | 8.2 |

| Public debt (% GDP) | 54.7 | 51.6 | 50.1 | 48.7 | 49.5 |

(e): Estimate (f): Forecast

STRENGTHS

- Port activity (Rotterdam is Europe’s largest port and the 10th in the world)

- Installation of home-grown international companies working with a dense network of SMEs

- Diversified and flexible exports (services account for 39% of total export revenue), external accounts in surplus

- Strong digitalisation

- High quality infrastructure and good living standards

WEAKNESSES

- Exposure to the European economy (Dutch export earnings represented 31% of GDP in 2020, 13% of the exports were re-exports), especially Germany and Belgium (25% and 12% of all goods exports 2022, respectively)

- High exposure to European gas prices that prompts more inflation volatility when gas prices fall or increase (gas represents 38% of total energy consumption; 71% of Dutch residents heat their home with gas)

- Debt of private households is very high (223% of disposable income in 2021)

- Ageing population, pension system under pressure

RISK ASSESSMENT

Modest growth only in 2023 and 2024

After a very strong recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic in 2021 and 2022 that was driven by strong private consumption(mostly for services) and good results from foreign trade, economic growth in 2023 and 2024 should be noticeably slower. In 2023, private consumption is unlikely to maintain the pace of the last two years – although the inflation rate eased noticeably during the year – due to a fall in European energy prices. The translation between energy prices and inflation is swift as gas is the main source of heating in the Netherlands and 3.5 million households (44%) have only have a short-term heating contract (6 months) so that prices adapt quickly. The Dutch government previously implemented an electricity and gas price cap, which also helped to bring down energy prices. Production in the Groningen gas field of has deteriorated markedly and will end in October 2023. However, by then, energy supply will be secured by two LNG terminals in Eemshaven and Rotterdam. In combination with full gas storage levels (88% in late July 2023), scarcity of natural gas in winter 2023-2024 and the related increase in natural gas prices will be less likely. This means that the inflation rate should even out to between 3.0 and 2.5% in 2024 when the basis effects from the energy crisis will have disappeared and the impact of ongoing high service and food prices should hold the inflation rate at a relatively high level. Household purchasing power will have strengthened and is expected to continue increasing in 2023 and 2024, thanks to higher collective bargaining agreements that have included wage rises of around 10% for many sectors in 2023 and will be supplemented by further smaller increases in 2024. The ongoing low level of unemployment has prompted and should further encourage unions to ask for higher wages. The minimum wage grew by 10% in January 2023, and by another 3.1% in July 2023. It is expected to increase further in January and July 2024, albeit by a lower margin. Nevertheless, private consumption (43% of GDP) should remain subdued as it has chiefly relied on a reduction in the savings rate in recent years. In Q2 2023, the savings rate of private households fell to 17.5%, which is the lowest level of the time series (started in Q3 2019). House prices declined by 6% in the first half of 2023 and the expectation of durably high interest rates should also lead to more hesitant spending behaviour. In 2024, when wages increase further and faster, private consumption should pick up slightly again.

Private construction and corporate investment should also remain subdued in the second half of 2023 and the first half of 2024 as higher financing costs weigh on activity. Between January and July 2023, the European Central Bank (ECB) had increased its key marginal lending rate four times by 175 basis points to 4.25%, i.e., one of the highest levels in the central bank’s history. With Dutch and European inflation on the downtrend, the ECB should go into a “wait-and-see” mode. The initial rate cuts are not likely to occur before mid-2024. In terms of quantitative easing, the ECB already stopped reinvestments of its APP program in July 2023. The maturing papers under its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP) have been fully reinvested until at least the end of 2024. Less support for economic growth should also come from the public side. The state should spend more on digitalisation and environmental actions through the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility in 2023, but for 2024 the government will probably adopt harsher austerity to bring down the deficit further. Foreign trade – exports account for 89% of GDP, and imports 77% in GDP – should represent only a modest growth factor in 2023 due to stagnating activity in Western Europe, but could pick up somewhat in 2024. Taken together, the quarterly growth rates of the Dutch economy should be noticeably higher in 2024 than in 2023. However, due to a positive carry-over effect from the year 2022 to 2023, this is not directly visible in the yearly GDP growth rates for 2023 and 2024.

Public deficit set to decrease

Although the Dutch government is generally on an austerity path, 2023 will end with a public deficit due to the state energy subsidies that will terminate at the end of the year. Furthermore, tax income will be lower due to the lower growth outlook. In 2024, the public budget will improve somewhat, but remain in a deficit for another year. Public debt is decreasing as a share of nominal GDP thanks to the durably robust growth in GDP that is not price-adjusted.

The Dutch current account registered two very strong surpluses in 2021 and 2022. They are mainly linked to the balance of international investments revenues, which, from its structural deficit, switched to positive in 2021. This phenomenon can be attributed to the transfer of Shell’s headquarters from the Netherlands to the United Kingdom at the end of 2021, which changed the direction of these revenues. This effect already levelled out somewhat in 2022 and will fully dissipate in 2023. Therefore, the current account surplus should decrease slightly in 2023, but still remain high. In 2024, the goods trade surplus should again benefit from higher export volumes, while only minor changes are expected to the services surplus and the structural deficits of investment trade and the balance of transfer of assets.

Elections in November 2023 likely to shake up Dutch politics

Mark Rutte of the conservative-liberal party VVD has been leading a caretaker government since July 2023. His government coalition formed from of the VVD (34 out of 150 seats in the House of Representatives), the Social-Liberal D66 (24 seats), the Christian-democratic CDA (14 seats) and the Centrist CU (5 seats) broke up over a dispute on immigration. While the VVD and CDA supported a stricter asylum policy, which would noticeably reduce the number of asylum seekers allowed to bring their families with them, the D66 and CU blocked it. This coalition was the fourth in a row under the leadership of Rutte since 2010. It took a record time of almost 10 months to form a coalition after the last general elections in March 2021. After the coalition broke up, new elections were announced for 22 November. Rutte and the leaders of the CDA and D66 announced that they would no longer run for election. Political themes have changed since the last general elections in 2021: the EU nitrates directive to drastically reduce nitrogen emissions became a major controversial issue. The Netherlands has to reduce its emissions by 50% by 2030. This requires a significant reduction in livestock and means the end of about 30% of farms in the Netherlands. The BBB (Farmer-Citizen Movement) developed in 2019 out of the farmers’ protests. After securing only 1% of the vote in 2021, they won by a landslide at the provincial elections in May 2023 and, with 19.2% of the votes, became the biggest faction in the provincial councils as well as the largest party in the Dutch Senate. However, while the BBB had been well ahead in the polls from March 2023, support weakened immediately after the announcement of fresh general elections when it became clear that the leaders of the movement do not see themselves governing the country. The social democrat Labour Party (PvdA) and the environmentalist Green Party (Groen Links), both smaller opposition parties, formed an election alliance. In summer 2023, with their new leader Frans Timmermans, Vice-President of the EU Commission who stepped down to become candidate, the new alliance was leading the polls with 18% of the vote, followed by the VVD (17%) and the BBB (16%). The election outcome is highly uncertain, but if the BBB wins, it could form, together with the nationalist PVV, the first right-wing, anti-EU government of the Netherlands.

Last updated: October 2023

Payment

In the Netherlands, bank transfers are by far the most common payment method for both domestic and export business-to-business transactions. All Dutch banks are linked to the SWIFT electronic network, which provides low-cost, flexible and rapid processing of international payments. Direct debit and different centralised local cashing systems are also widely used. Online sales are increasingly popular and most companies now use digital banking software. Cash payments are gradually disappearing and other payment methods, like cheques and bills of exchange are rarely used.

Debt collection

Amicable phase

A debt collection process usually begins and ends by sending the debtor a (sometimes registered) collection letter. Sending letters (only) by email is becoming more and more customary. Besides the principal claim amount, the collection letter usually also includes a demand to pay accrued interest and extrajudicial costs. If the interest rates and/or costs have not been agreed by contract, Dutch law regulates the limits for both. If amicable actions, which include reminders by phone and possibly a debtor visit, do not result in full payment, the creditor can initiate legal action, in accordance with Dutch civil law.

Legal process

Fast-track procedures

In urgent cases, claims can be submitted for a fast track procedure (kort geding). These proceedings resemble those of the regular civil court but, if convinced of the plaintiff’s arguments, the judge (ruled by the President of the district court) delivers a verdict within a very short period of time – usually between two to four weeks. During this somewhat simplified procedure, the judge often makes a temporary or provisional ruling for more urgent matters. If, subsequent to this provisional decision, the parties do not reach a final settlement on all issues, they then need to obtain a final judgement in a “regular” civil suit (bodemprocedure). The fast track procedure in the Netherlands differs from the (European) payment order procedure used in many other European states. It always requires the assistance of a lawyer and personal appearances by all parties before the judge. As this makes the fast track procedure rather expensive, it is not often used in regular collection cases.

Ordinary proceedings

The regular civil court procedure, held in one of the eleven district courts (Rechtbank), is the most frequently used recourse of action. Claims of €25,000 or less are heard by a judge of the cantonal sector of the district court (kantonrechter), while claims in excess of €25,000 are presented before the civil law sector. The main difference in the civil law sector is that both the plaintiff and the debtor have to be represented by a lawyer, whereas in the cantonal sector parties are permitted to argue their own cases. Both types of procedures begin with a bailiff serving the debtor with a writ of summons. In many cases, debtors do not contest the claim or appear in court. This results in a judgment by default being given, usually within six to eight weeks. If the debtor does appear in court, the judge sets a date for them or their lawyer to prepare a written statement of defence (conclusie van antwoord). However, when appearing before a cantonal sector judge, debtors can represent themselves and plead their cases verbally. After the first plea, it is standard procedure for the judge to schedule personal appearances by both parties to obtain more information and to see if a settlement is possible (comparitie van partijen). If not, the court can either pass judgement immediately or, in more complex cases, give the plaintiff the opportunity to deliver a replication (conclusie van repliek). The defendant can then reply by rejoinder (conclusie van dupliek). These proceedings take, on average, six to twelve months.

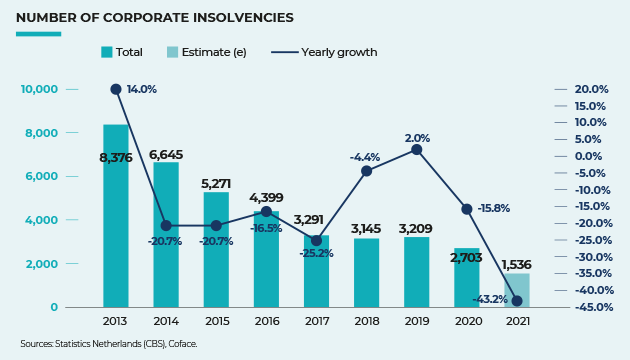

Winding-up proceedings

A third and often effective procedure for collecting payments is by filing a winding-up petition at the district court. This type of petition must be filed by a lawyer and the applicant needs to submit evidence of a payment default on an undisputed debt and of the existence of at least one other creditor having an undisputed claim of any kind (for example, commercial debt, outstanding alimony or taxes). The debtor is then formally notified by a bailiff that a winding-up petition has been filed. To avoid bankruptcy, the debtor can choose to appear in court to dispute the claim (or the fact that there are other creditors) or propose an out of court settlement. As most debtors try to reach a settlement, these proceedings are often cancelled before the date of the court hearing. Otherwise, and if there is sufficient evidence, the debtor is then declared bankrupt. Approximately 95% of all bankruptcies result in no payment being received by non-preferential creditors.

Retention of title and right of reclamation

Besides initiating legal action or claiming retention of title (if stipulated), sellers of goods can often exercise their right of reclamation (recht van reclame) for unpaid goods. This entails sending the debtor a registered letter which invokes this right. The contract is thus terminated and by law, ownership of the goods returns to the creditor. However, this recourse of action does require the goods to be in their original state. The registered letter must be sent within 6 weeks of the claim being due and within 60 days of the goods being delivered.

Enforcement of a legal decision

If a debtor does not voluntarily comply with a court decision, the creditor can initiate actions to enforce the judge’s ruling. As most court decisions become effective immediately, creditors do not need to wait for the three month period of appeal to expire. Enforcement laws lay down statutory rules on coercive measures and how these measures can be applied. In the Netherlands, only bailiffs are authorised to levy enforcements and are instructed by the creditor. Two conditions need to be met before coercive measures begin. The bailiff must be in possession of a writ of execution (an original and enforceable judgment) and the party on which the enforcement will be levied must have prior official notification of the writ.

Court decisions rendered by other EU countries benefit from specific enforcement mechanisms, including the EU payment Order and the European Small Claims procedure. Decisions issued by non-EU countries can be recognised and enforced on a reciprocal basis, provided that the issuing country is part of a bilateral or multilateral agreement with the Netherlands. In the absence of such an agreement, an exequatur procedure can be carried out in the Dutch courts.

Insolvency proceedings

Restructuring proceedings

Corporate debt restructuring entails using the suspension of payments (surseance van betaling) procedure. The debtor is granted temporary relief from creditors, in order to allow them to reorganise, continue with business operations and ultimately satisfy their creditors’ claims, all under the supervision of a court-appointed administrator. A plan is proposed and must be approved by two-thirds of the creditors representing three-quarters of the total outstanding debt.

Bankruptcy proceedings

The debtor’s assets are liquidated by the court-appointed trustee. This procedure commences when the debtor has ceased payments and the District court has declared the debtor bankrupt. If a creditor makes a request for the debtor to be declared bankrupt, there must be at least two creditors with overdue claims. However, when liquidation is requested by the debtor, evidence of additional creditors is not mandatory.

The trustee establishes a list of creditors, the debtor’s assets are auctioned and the proceeds then distributed between the creditors.